The Little Engine That Survived - Our 1905 Shay Engine, #1568 or Engine 19

Many people ask us for a complete history of the locomotive that stands proud in Harrod. The problem is like many historic artifacts this engine has seen a lot, is well traveled, and has changed ownership many times, much of which was not documented. The following is a collection of photos and information gathered from many sources on the history of Lima Locomotive Shay Engine #1568; the crown jewel of Harrod, Ohio and its history.

Original Lima Locomotive photo of the September built 1905 Shay Locomotive for Tioga Lumber Company, Nicholas County, West Virginia

In 1882, Ephraim Shay assigned the rights of the locomotive that would bear his name to a company that would eventually become Lima Locomotive Works, Lima, Ohio. Shays’ could burn coal, oil, or wood, and varied from tiny two cylinder, two truck models to three cylinder, four truck monsters weighing over 400,000 pounds.

The Shay produced a distinctive sound. The rapid firing of the cylinders made it sound like it was going about 60 mph when it actually chugged along at only 12 mph! The locomotive was capable of climbing grades as great as 14 percent.

Shay Locomotives were produced until 1945. There were 2,771 Shays built, of which approximately 84 still exist. It’s a testimony to the Shay design and quality that many of these remain in active service, most in tourist railroads.

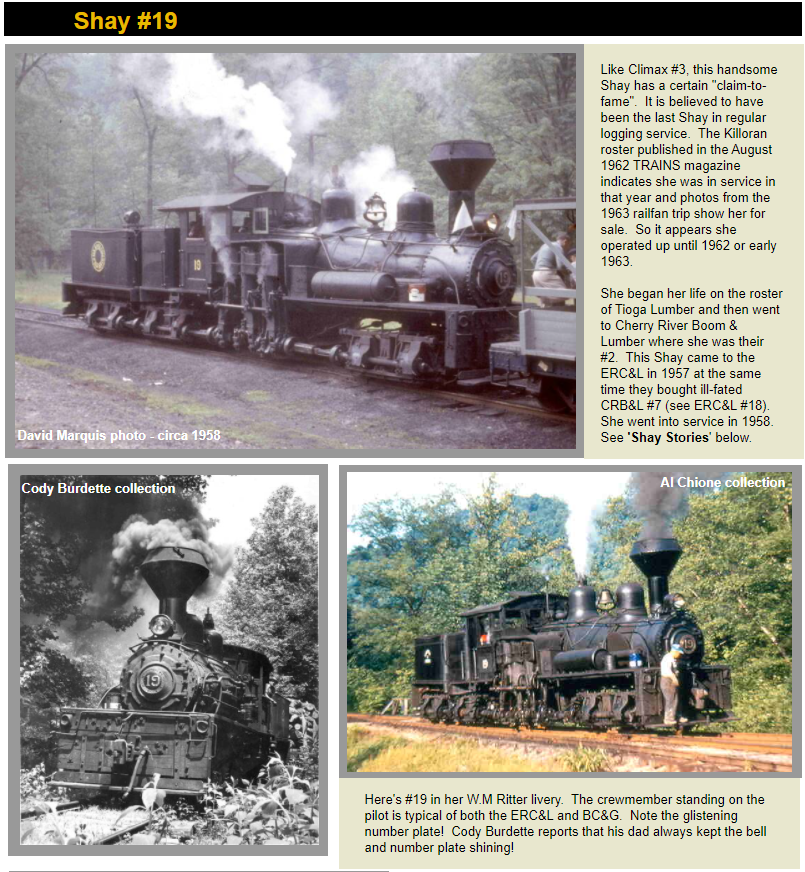

The Shay engine displayed in Harrod was manufactured in September of 1905 at the Lima Locomotive Works, Lima, Ohio. It was built for the Tioga Lumber Company, Nicholas County, West Virginia and was designated Loco #1568. It was owned by several lumber companies over the years and in 1963 was reported to be the last Shay engine operating in daily log train service in the country. The Georgia-Pacific Lumber Company owned the engine at that time.

Shay Loco #1568 was purchased in 1964 and moved by truck to Wytheville, Virginia where it was operated in a theme park called Dry Gulch Junction at Big Walker Mountain until 1972. In 1978, the Shay developed a throat sheet crack and the expense to repair it was more than the struggling operation could bear. That was the last time the locomotive was under steam.

Another entrepreneur with the intention of developing a tourist railway purchased the Shay. Unsuccessful attempts to secure a right-of-way for the proposed project ended that endeavor and the Shay was sold to a Florida shipyard owner. Details are very sketchy in this chapter of the engine’s life. There were rumors at one point that it had been cut up and sold for scrap. Apparently those rumors were started to deter vandalism and theft of parts from the engine. In 1992, an advertising circular from a North Carolina dealer, keeping the secrecy of the exact whereabouts of the engine, listed it for sale and ended speculation about its demise to the scrap pile.

American House, Inc., Created to preserve Lima history and cultural heritage, purchased the engine and transported it from Mossy Head, Florida to Lima, Ohio. A commendable effort was made to chronicle the Lima Locomotive Works and its workers but they elected to disband in 1996 and the Auglaize Township Historical Society was given the opportunity to purchase the Shay Engine. In doing so, an important part of our local history and heritage was kept in the Lima, Ohio area where it was manufactured so many years earlier. The Shay was dismantled and transported by truck from Lima to its present location in Harrod, in 1996.

These pictures were sent to us by Everett Hovencamp. Everett and his wife visited the Harrod Railroad Heritage Park in the summer of 2022. Everett has a treasure trove of information about our Shay Engine. The above picture is our Shay, whereabouts unknown, hauling logs. He said that the tracks were laid when it was dry but the Shay could still work if it was flooded.

The above two photos are from when it was working at the Dry Gulch Junction Amusement Park (more information below). The gentleman on the ground next to the Shay is Sam Lantern, who went on to work at the Grand Canyon Railway. Everett believes Sam was from Indianapolis. The gentleman standing in the cab is Stephen Hamilton, who passed away in an accident involving the Shay. Everett was a little boy when his dad was employed by the Amusement Park to build all of the buildings at the Dry Gulch. He said he used to shovel coal into the firebox of the Shay.

Dry Gulch History and Engine #19

Engine #19

The Old Shay #19 (1905 Shay Engine) has a history of its own before even coming to Dry Gulch. The engine was made in Lima, Ohio, in 1905. The first owner was the Tioga Lumber Company in Nicholas County, West Virginia. The Tioga became the Birch Valley Lumber Company in 1915 but engine ownership was not to last. The Shay was again sold to Hookersville’s Sutton Company in 1925. It was sold to the Cherry River Boom & Lumber Company in about 1927, which operated out of Richwood, West Virginia.

The next owner was the Ely-Thomas Lumber Company. Unfortunately, dates for this transaction have been difficult to locate. The engine then went to the Elk River Coal & Lumber Company, in 1957, where it became Engine #19.

While there, the engine, and the company, saw a number of new owners. First, the W.M. Ritter Company, and then, Georgia-Pacific.

While working at the lumber mill, a fire burned the original cabin away. The workers just replaced it with a cab from a #18. It also froze to the rail during winter. One worker claims he had to open the throttle and reverse the engine to break the ice.

Stuart Kime purchased the engine in 1964. The train ran until 1972, when Kime died. It was replaced with a rod engine. The rod engine was sold in 1977, and the Shay returned to its tracks. The Shay remained running until 1979.

Life for the old Shay engine becomes sketchy after Kime’s ownership. It passed through a number of owners before being moved into storage, or so it was reported. It remains unclear as to where this information came from. According to several reports in the 1990s, the engine was in storage, pending restoration. It was supposed to become an exhibit piece. Several reports claimed the engine had returned to its original owner, the Lima Locomotive Works, which then operated as the Lima Trade Center. The primary issue is that the Lima Trade Center closed in 1981. During the 1970s, it was a branch of the Clark Machine Co.

The Shay #19 is now on display in Harrod, Ohio at the Harrod Railroad Heritage Park.

History of Dry Gulch

Stuart Thomas Kime was originally an engineer. After working on an Ozark tower in Arkansas, the Pennsylvania native decided he wanted such a place of his own. As World War II was ending, he found the perfect spot for a tower. He purchased some land on the Wythe-Bland County border.

He first opened a gas station and gift shop in 1947. He constructed the original 50 ft. tower by himself, around 1953. He then hired a crew of steelworkers to add another 50 ft. The Big Walker Lookout was ready for guests.

Kime’s wife, Abigail, opened the Pioneer Dining Room Restaurant nearby. The restaurant had a 4,000 square-feet basement that became the Kime home. Sadly, the restaurant and Kime home burned to the ground in 2003.

Kime added a chairlift in the 1960s, but the insurance became too expensive. They had to close it. They also had a poisonous snake attraction, but that too disappeared.

Kime wasn’t through building, nor ready to give up the notorious Appalachian Tourism Gambit. He wanted another attraction. He decided to purchase a train, and bought the Shay Engine #19 from a company in West Virginia. He laid a half mile of railroad track and wanted to eventually lay 4 miles. He named the attraction “Dry Gulch Junction and Tombstone.”

Dry Gulch and Tombstone

Kime knew it was going to be risky venture but attempted it anyway. He even went to Roanoke, in June of 1966, to request more funds for the highway. Kime was the president of a group called the Great Lakes to Florida Highway Association. This group was devoted to growth and development along Route 21, the main road connecting Ohio with Florida. The Great Lakes to Florida Highway Museum is in Wytheville.

Dry Gulch was originally just a scenic excursion, somewhat of an extension of the Big Walker Lookout observation tower a few miles away. Kime launched the attraction in 1966. Dry Gulch Junction became a notable county attraction in the 1970s. The train was added to demonstrate the typical logging trains used in the Appalachians at the turn of the Twentieth Century. Kime moved an old chestnut mill from Little Creek. The machinery was still functional.

Ownership of the attraction was never an easy task, even at its inception. Highway US-52 would be its undoing. The highway opened in 1972, and directed traffic away from Kime’s efforts. As if that wasn’t hardship enough, his old Shay engine derailed and he died on November 8, of that same year.

The attraction closed while the family considered their options. One year later, Dry Gulch re-opened with a different engine. Kime’s wife, Abigail, and son Ron were the managers. It was then that Ron considered expanding the attraction. He eventually developed plans for constructing a proper town around the tracks. The historic town opened in 1977, as Dry Gulch Junction. There were “Wild West” shootouts and similar performance artists throughout the town. Sadly, the bad luck didn’t stop.

The site then featured numerous 19th Century structures, such as a general store, chapel, and a jail. The structures in Dry Gulch each have their own history.

Bad News, Worse News

Stephen Hamilton was a Chicago native, who worked at Dry Gulch Junction for two years. He was a graduate of Ball State University. He died when the train ran him over on July 15, 1979.

According to historians, Dottie West sang in Dry Gulch during the late 1970s. During this period, Dry Gulch hosted singers Helen Cornelius and Jim Ed Brown. They also claim the latter concert drew around 3,500 attendees.

Just when it seemed the little park might actually be a success, flooding came. It rained every time a show was put on. Once, historians claimed, it even snowed.

The Kime family was not to see success. They paid a great deal for major performers, when the attraction barely paid for itself. Several years later, family had a trustee’s sale, and lost Dry Gulch Junction. The train was dismantled, but the structures remained.

The place was abandoned and left to the elements, and vandals. It was privately owned for a time as a hunting sanctuary, but trespassers were common.

The Buildings

The town’s saloon came from Broadford. Many of the structures came out of Pocahontas. As years passed, the windows were broken and the paint faded. Thieves stole the copper from the buildings. It seemed like the end had come for the old venue.

Rising from the Ashes

A North Carolina couple, Michael Hill and Jeanne Davis, stumbled across the forgotten destination in 1998. The native North Carolinians had been searching for a place in Southwestern Virginia. They fell in love with the property, and the price was too good to pass by. Once they assumed ownership, they brought in a crew to restore the town to its original state. Their hard work paid off and they opened in 2000.

Eventually, they expanded to feature the Virginia City Gem Mine. This sheltered sluice allowed visitors to purchase buckets of ore to search for gems. The sluice was imported.

The Curse Strikes Again

Unfortunately, their hard work seemed to be just as futile as the Kime family’s hard work. The Curse of Dry Gulch never really left. Davis admitted they never received pay for their efforts. They estimated their investment was somewhere between $1-$2 million. They worked on the attraction daily for 10 years. They borrowed money, with their own home as collateral, and even sold off family land to support it.

Tragedy came again a few years later. Hill was on his ATV in 2006, and suffered an injury. He thought it was something trivial that would heal itself, like a torn ligament. His pain continued to worsen and by the time he went to see a physician, it was too late. He died shortly thereafter. As if one loss wasn’t enough, Davis’s own father died the next year.

After her father’s untimely death, she lost any desire to work further on the attraction. She started to put it up for sale in 2008 but didn’t. The only portion that was successful was the sluice mine but even that wouldn’t provide forever. The property went to the auction block in May of 2014. It was sold in September and Dry Gulch once again became private property.

Was Dry Gulch cursed? Rumors of its haunted structures continue to spread but perhaps the bad luck can be more aptly attributed to the wrong place at the wrong time. Like so many other attractions in Appalachian areas, Dry Gulch belonged in an era when the roads were smaller and the traveler wasn’t in such a hurry.

Sources:

Everett Hovencamp

http://www.buffalocreekandgauley.com/index.html

https://vacreeper.com

Thank you!